What Could Have Been: A Peek Into the Writing Process

Read a full character background that ended up cut from Victor in Trouble

A wise friend of mine once said, sometimes you have to cut your best stuff. It’s heartbreaking, but he was right (he went on to win a Pulitzer, so I guess he really does know something about writing). Some writing goes off on fun tangents that later render the prose difficult to follow. Some jokes are hilarious but ultimately the chapter is better when it is tighter. Snip! And there the joke falls to the cutting room floor. Sometimes those ideas can be modified and used elsewhere in the story; sometimes writers save them for another piece of work entirely.

Here’s one fun example: The original script for Raiders of the Lost Ark included a scene in which Indiana Jones goes to Shanghai and gets involved in a fight in a restaurant, running behind a gong while getting shot at. It also included a scene of Indy and Marion fleeing Nazis in mine carts. Neither scene made it into Raiders, but Steven Spielberg filed the ideas away for another day. When he made Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, both scenes were written into the script and made it into the movie.

Ah, what could have been…

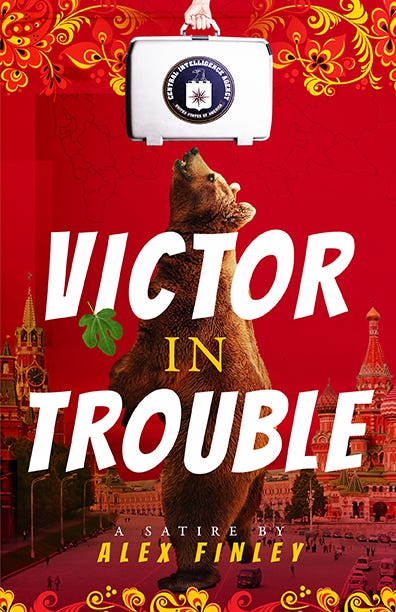

In that vein, I’ve decided to post part of an early draft of Victor in Trouble, my satirical novel that sends case officer Victor Caro to Rome for what he hopes will be a food-filled easy ride to the retirement finish line. But our hero soon uncovers a massive Russian influence operation aimed at weakening Europe and the United States. As a disinformation campaign pushes political dysfunction to new heights—leaving one US senator clamoring to ride a Russian bear after meeting a Russian, gun-slinging honeypot in stilettos—Victor finds himself enmeshed in a frantic effort to save democracy.

Below is character background for Victor in Trouble’s fictional Russian president, Darko Vlastov. There is so much I love about this, but also so much that just didn’t work as part of the whole novel. I had to cut parts and change things around.

If you’ve already read Victor in Trouble, see if you can spot what I saved from this draft and used differently and elsewhere in the story. If you haven’t read Victor in Trouble, what are you waiting for?? It’s even better than this draft excerpt!

RUSSIAN PRESIDENT DARKO VLASTOV

Character background cut from Victor in Trouble

Darko Vlastov was in a good mood. The 65-year-old president who had ruled Russia for nearly two decades leaned back in his high-back leather chair, his fingers clasped behind his head. His vast desk was nearly empty in front of him, save for a gold pen resting in the exact middle. Under the desk, one of his many secretaries crouched on her knees, giving him a blow job. A photo of him in his younger years hung on the wall behind him. The handsome 24-year-old wore a military uniform, his angular jaw and sharp cheekbones offsetting his big, round, blue eyes, which bore into the camera. The photo had been snapped in 1975, when he had joined the KGB. Never would that young Soviet patriot have imagined then that he’d be in this office one day, celebrating the election of a new American president. For generations, the holder of the Oval Office had been one of Russia’s main enemies, but now, Richard Redd was poised to change that. He spoke of renewing relations between the two countries and accepting Russia, rightfully, as an equal superpower. Vlastov grinned, for he had helped orchestrate Redd’s surprise victory. He couldn’t take sole credit, of course, although he would accept it if someone wanted to assign it to him. America was ripe to be toyed with, the societal fissures already apparent—gun rights, gay rights, vegan rights—just waiting for him to shove a wedge in and crack the country wide open. He might also deny having anything to do with it. Whatever was most useful in a given situation. Nor did he relish helping Redd, the buffoon. But he was so easy to manipulate. An ego stroke here, a dick stroke there. Even if Redd didn’t follow Vlastov’s lead precisely, he was sure to engender righteous anger from all sides. Which was why Vlastov knew he would make a good tool to achieve his long-held objective of knocking the mighty United States down a peg.

All of his experiences, his victories and his failures, had contributed to this moment. He savored the memories of how he had arrived here. He had decided on the KGB path at a very young age, after seeing the film “Spy Me Up, Spy Me Down.” The main characters of Georgy Markov and Peter Averin had caught his imagination with their cool and methodical takedown of a CYA spy, and driving a Volga with a racing stripe became a major aspiration for the young Darko.

After he joined the service, he was posted to East Germany. He was ecstatic. He could hardly wait to discover Berlin, the divided city that had become the epicenter of the Cold War. He had heard the stories from his elder KGB comrades about rooting out traitors in local East German security services or recruiting assets to infiltrate pro-Western groups. He had imagined himself lurking in the shadow of the Brandenburg Gate, skulking along tunnels that penetrated into West Berlin, welcoming defectors, training them, and sending them back to take down the enemy from the inside.

The reality had been more mundane at first, Darko admitted to himself, remembering how he had spent most of his days translating newspaper articles and filing paperwork. The masters in Moscow were very meticulous about documenting every action of their officers. Party leaders enjoyed knowing how productive the KGB was. Lower level leaders needed excellent numbers to impress their superiors, who in turn needed excellent numbers to impress their superiors, and so on all the way to the general secretary of the Communist Party, who was always very impressed with the excellent numbers. Since it was Darko’s first tour, the boss had given him the task of documenting those excellent numbers.

The KGB office in East Berlin did not give Darko a Volga with a racing stripe, but it did issue him a used Trabant, a car designed and manufactured in East Germany. Its exterior was made out of a hard plastic—East Germany had limited metal supplies—while its engine was like a polluting lawnmower that made a loud breeeeeee sound, even when the car idled. That, combined with the car’s bright green exterior, made it a little too conspicuous for skulking in the shadows. The Trabi was no Volga.

After two years in Berlin, Darko had not gone mano a mano with a CYA spy, despite his highest hopes. He spent much of his time in a bar near a checkpoint to the West. It was always full with West Berlin teenagers, who could easily cross back and forth between east and west and who enjoyed the cheap beer their western cash could buy. One group had given the bartender a cassette tape of the Bee Gees. The bartender played “How Deep Is Your Love” on a never-ending loop. He could have busted the bartender for subversion, but he had helped Darko restart the Trabi on too many cold nights when the motor felt fussy. Besides, he liked how the insidious disco music made him seethe against his enemies.

Those were dark days. One day, Vlastov remembered, he was eating a cookie at his desk while translating a technical article about West German agricultural soil treatment, when he broke down. Markov and Averin, the super KGB spies of the silver screen, never filed paperwork, even when they scratched the Volga. And the Volga was a real car, unlike his toy car that blew black smoke out the back and whose windshield wipers kept flying off. Nor had he ever been issued heat-sensing shoes or a walking cane that was actually a jet pack.

President Vlastov, getting a blowjob from his secretary, shook his head at the memory of his pathetic younger self, then smiled as he recalled his epiphany at that, his lowest moment. Weeping into his cookie crumbs, young Darko had realized “Spy Me Up, Spy Me Down” had made him believe in the legend of KGB officers, even if the truth was not as romantic. He thought of his bright green Trabi that refused to start if there was the slightest bit of humidity or if it was a Tuesday. He needed his own legend. For the first time, Darko understood the usefulness of a narrative and the importance of controlling it.

From that day on, once he had completed his bureaucratic duties, he explored the East Berlin underground and sought out soft spots he could penetrate, determined to rewrite his own narrative. He found ways to infiltrate anarchist groups, pro-democracy groups, and other resistance forces gathering steam against the communist government. He developed networks to launder money in order to pay his assets—his assets wanted US dollars or Deutsche marks from the West, not the East German mark knockoff. He used the same networks to smuggle goods. He tested the networks with small items for himself. That was how he got his first toaster. But over time, those networks grew, so that he was bringing in Western technology—computer and electronics parts, for example—for the engineers back in Moscow to tear apart and study.

Over the next several years, Darko kept his head down and worked his way through the KGB bureaucracy. He was an obedient and loyal member of the Communist Party, but quietly kept tabs on each of his comrades, noting every dismissive sniff, every feeble handshake, every miniscule action that could be interpreted as disloyalty or weakness.

Which is why he did not like Mikhail Gorbachev. He viewed the man who would become the last leader of the USSR as weak. Gorbachev’s conciliatory talk, his advocacy of opening up the Soviet Union and relaxing its grip on its satellite states to the west, made him too human, too easy to criticize, too easy to defeat. People wanted the myth. They wanted legends. As history barreled toward the final decade of the twentieth century, as revolutions shook countries up and down the Eastern bloc, as citizens of Hungary streamed over the border into Austria, and as East Germans climbed and tore down the Berlin Wall, Darko understood the impotent leader’s fatal mistake. Gorbachev had lost control of the narrative. Darko determined never to do the same.

In the chaos of the disintegration of the Soviet Union, the resourceful Darko saw opportunity. He moved back to his hometown of Leningrad, which had been recently reminted Saint Petersburg. The new mayor was an old family friend who welcomed Darko into his political circle. Officially, Darko Vlastov left the KGB at that point. He laughed to himself at the memory, causing his crouching secretary to glance up. He glared down at her and she immediately returned to her business on his business.

Unofficially, of course, he continued to maintain and extend his KGB network. He also perfected his backstory during this timeframe. It was in these years that stories of his heroic feats in East Germany began appearing in newspaper profiles of him. His mind-numbing work translating technical journals got recast as “providing sensitive technical intelligence.” His driving around East Berlin in a fart of a car was described as “Vlastov’s innate capacity to assimilate and blend in to any operational environment.” It was yet another example of Darko’s belief that controlling the narrative was paramount.

In Saint Petersburg, Vlastov also developed ties within Russia’s burgeoning business class. In charge of the city’s foreign outreach and business development, the mayoral assistant worked to attract foreign investment and was well placed to witness the transfer of state assets into the hands of a select group of private individuals. Russia was something of a wild west at the time, and the politically well-connected were about to thrive in the chaos. He was present when one colleague sold a shipping container full of Kalashnikovs to an African freedom fighter for twenty-five cartons of French cigarettes. He had taken note when Nikolai Surikov bought RosGaz for fifty-two dollars. Utilizing a technique he had learned in his years at the KGB, he also kept a file on each of them, full of compromising material. Most of it was true; some of it was false. The only fact that mattered was that Darko held these files, which scared a number of powerful and wealthy people.

The myth-building and networking paid off. In 1998, Darko Vlastov was named director of Russia’s Federal Security Service, or FSB, the new iteration of the KGB. In this capacity, he allowed his legend to really take off. Rumors spread that he could kill with one hand, that he had secretly been on Russia’s winning Olympic hockey team, and that he was more light-footed on the dancefloor than Fred Astaire.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Rant! with Alex Finley to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.